Motivation for Reasoning

Classical ML algorithms like Linear Regression, Support Vector Machines, K- Nearest Neighbours etc, have long served as powerful tools for narrow, well-structured problems, but what sets apaprt todays field of AI that distinguishes itself from the previous generation is the ability of todays models to reason (or do sometinig that resembels reasonig, quite convincingly i might add), the ideal of AGI (artificial general intellingence) is a computer that can reason and plan ahead, and current llms can be taught to do many things, this just comes under the paradigm of prompt engineering.

The ability to reason,

lets just assume that you are in 2017, before LLMs were mainstream, and you wanted to sovle the following problem,

Last Letter Concatenation

| Input | Output |

|---|---|

| “Elon Musk” | “nk” |

| “Bill Gates” | “ls” |

| “Donald John Trump” | ? |

Rule: Take the last letter of each word and concatenate them.

(Even thought this is a toy problem, this can provide us with the fundamental concepts necessary to understand how LLM reason)

So most people would collect vasts amount of data to and try and train a model that can do this simple task, So this is just a massive waste of time and resources, even though a human can write a simple program to solve this, but it would take a ML model a few thousand examples to get it right

Enter LLMs

For the first try most people will try and do something like this:

Input:

Rule: Take the last letter of each word and concatenate them.

“Donald John Trump”

Response:

pTrump

So from “Language models are few-shot learners” we know that LLMs can give you a correct answer based on a few examples, lest see how does the LM do now?

Input:

Rule: Take the last letter of each word and concatenate them.

“Elon Musk”: “nk”

“Bill Gates”: “ls”

“Donald John Trump”: ?

Response:

“Donald John Trump”: “mp”

(Expirements performed using the google/gemma-2-9B-it model, released June 27 2024, on togeather.ai, The above zero shot and few shot work on todays massive llms like GPT4o, and Claude 3.5 Sonnet.)

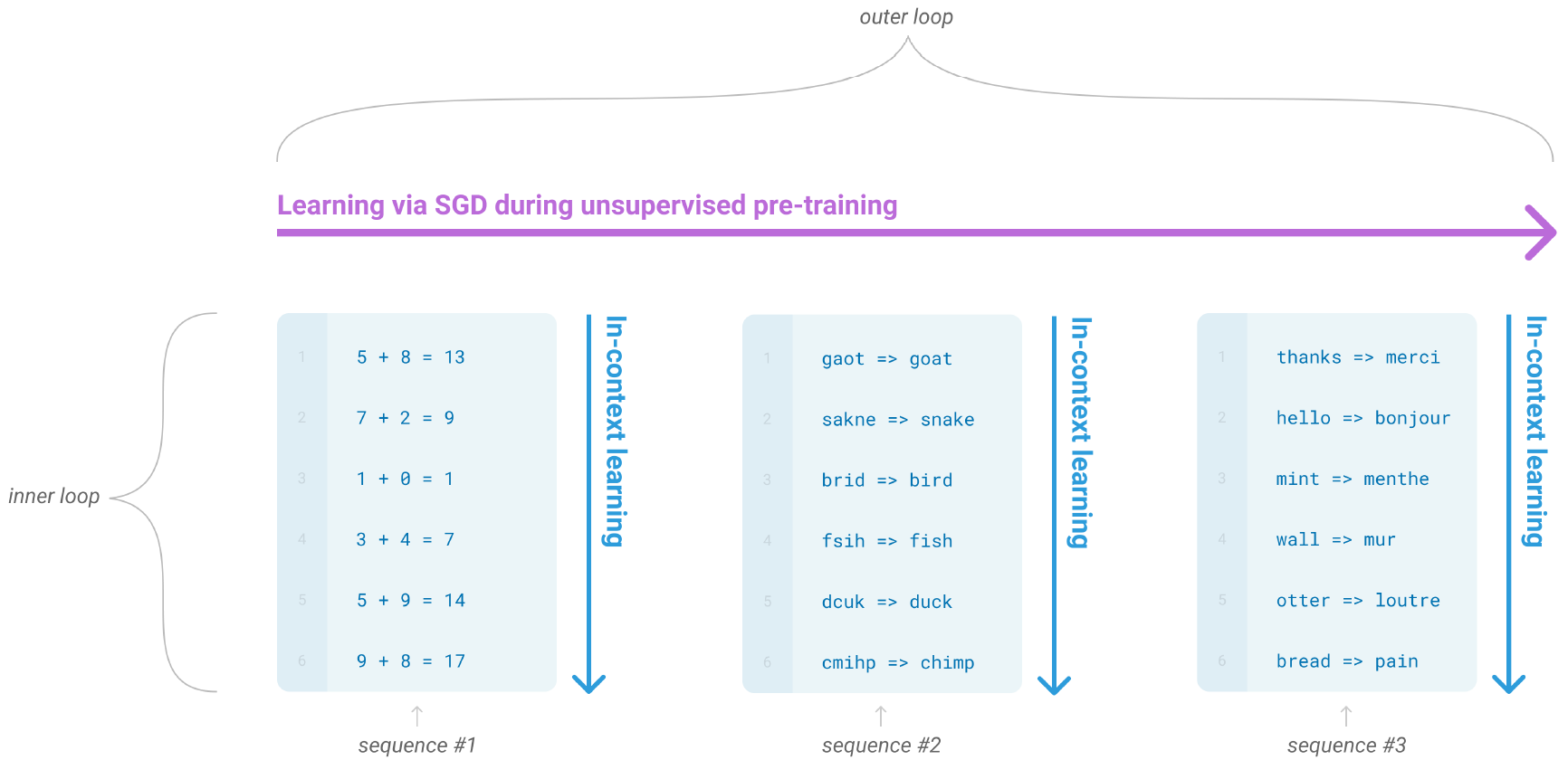

So why does techniques like few shot learning actually work? The technique of few shot learning was so powerful, and paradigm shifting when the researchers came across it, they named their GPT3 paper “Language Models are Few-Shot Learners”. Here they provide some reasoning as to why something like Few shot learning actually works, it is called in-context Learning

In context Learning

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

During the pre-training stage, a language model develops a broad set of skills and pattern recognition abilities. It then uses these abilities at inference time to rapidly adapt to or recognize the desired task. We use the term “in-context learning” to describe the inner loop of this process, which occurs within the forward-pass upon each sequence.

In Context Learning

As we can see, the model was not able to recogonize the pattern, so instead of concluding that this cannot be solved by the LM, researchers rolled up their sleevs, and started tinkering with the model.

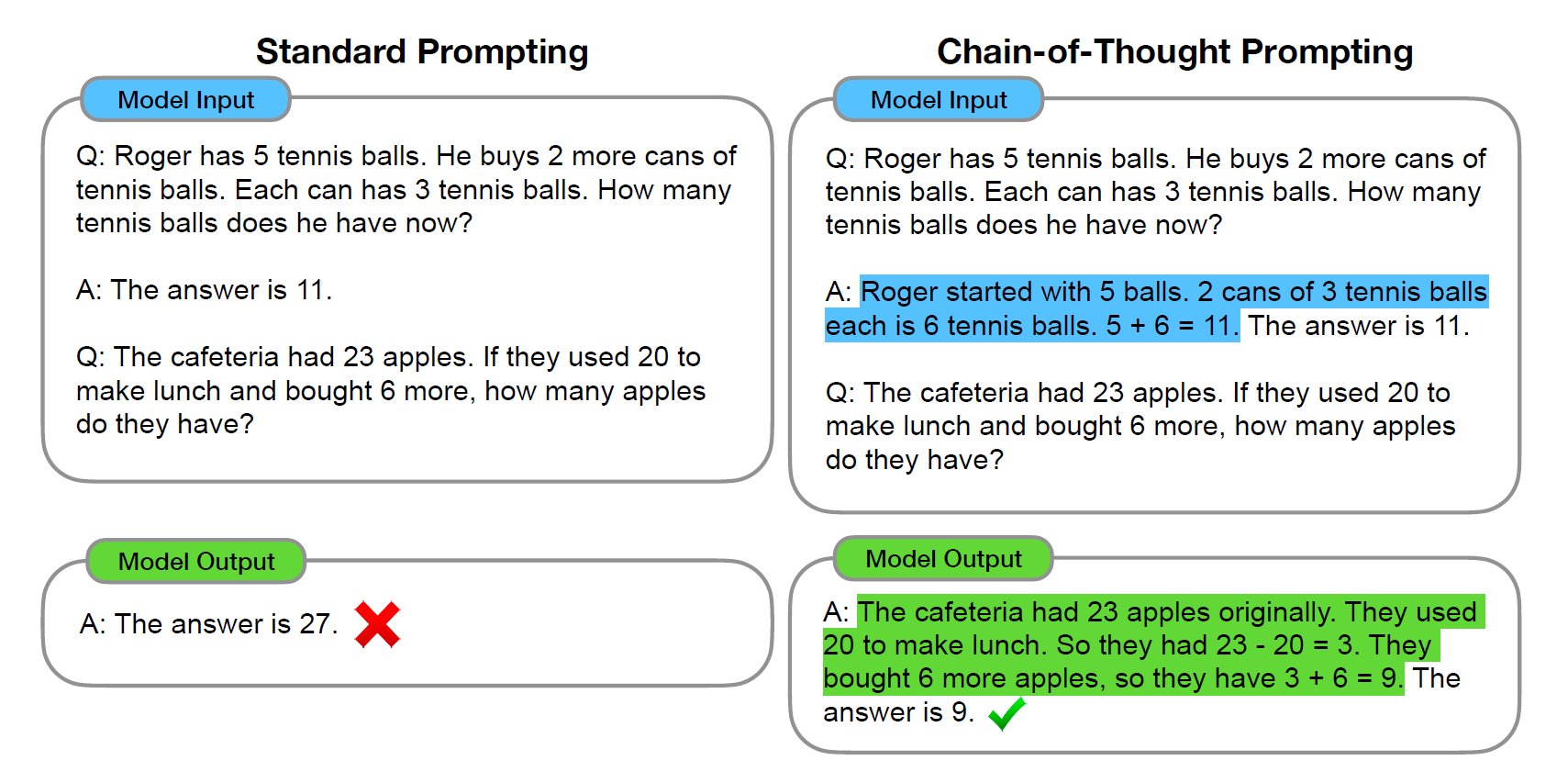

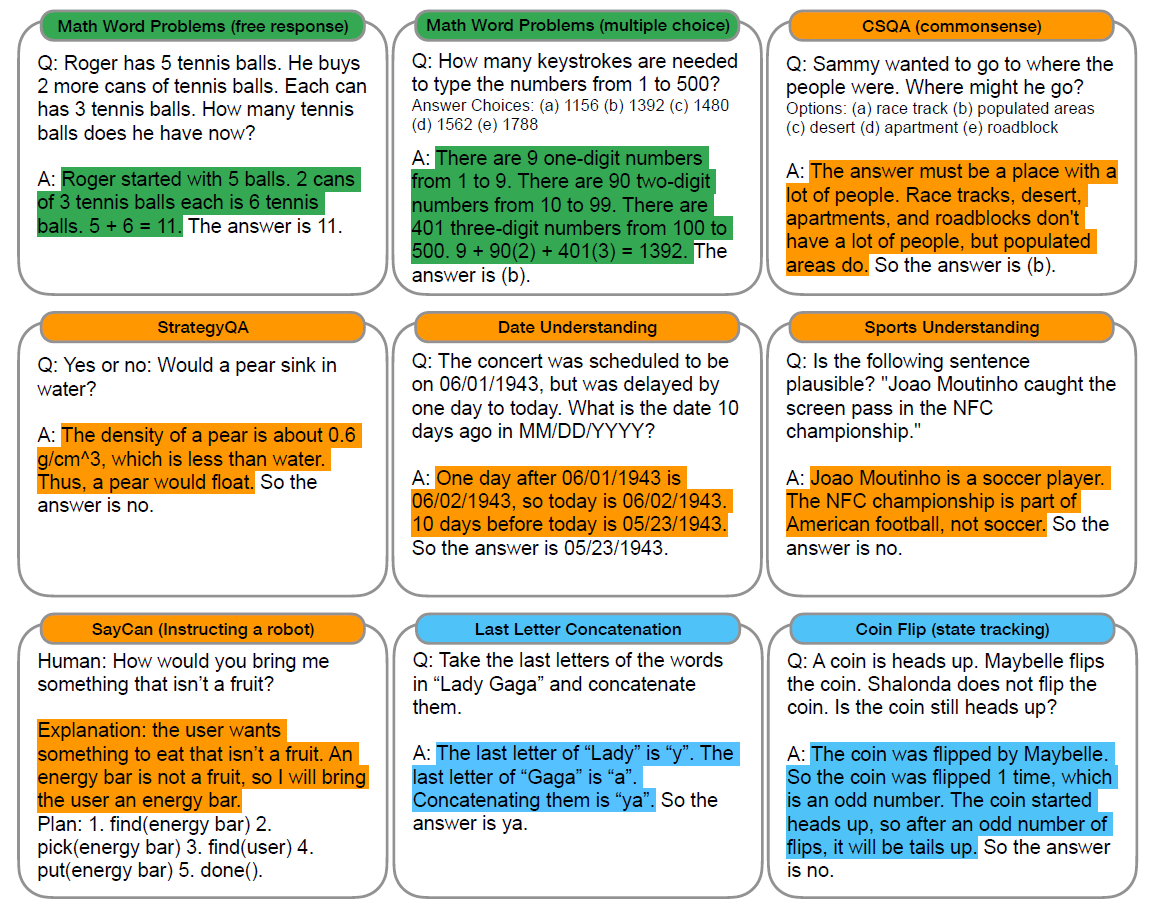

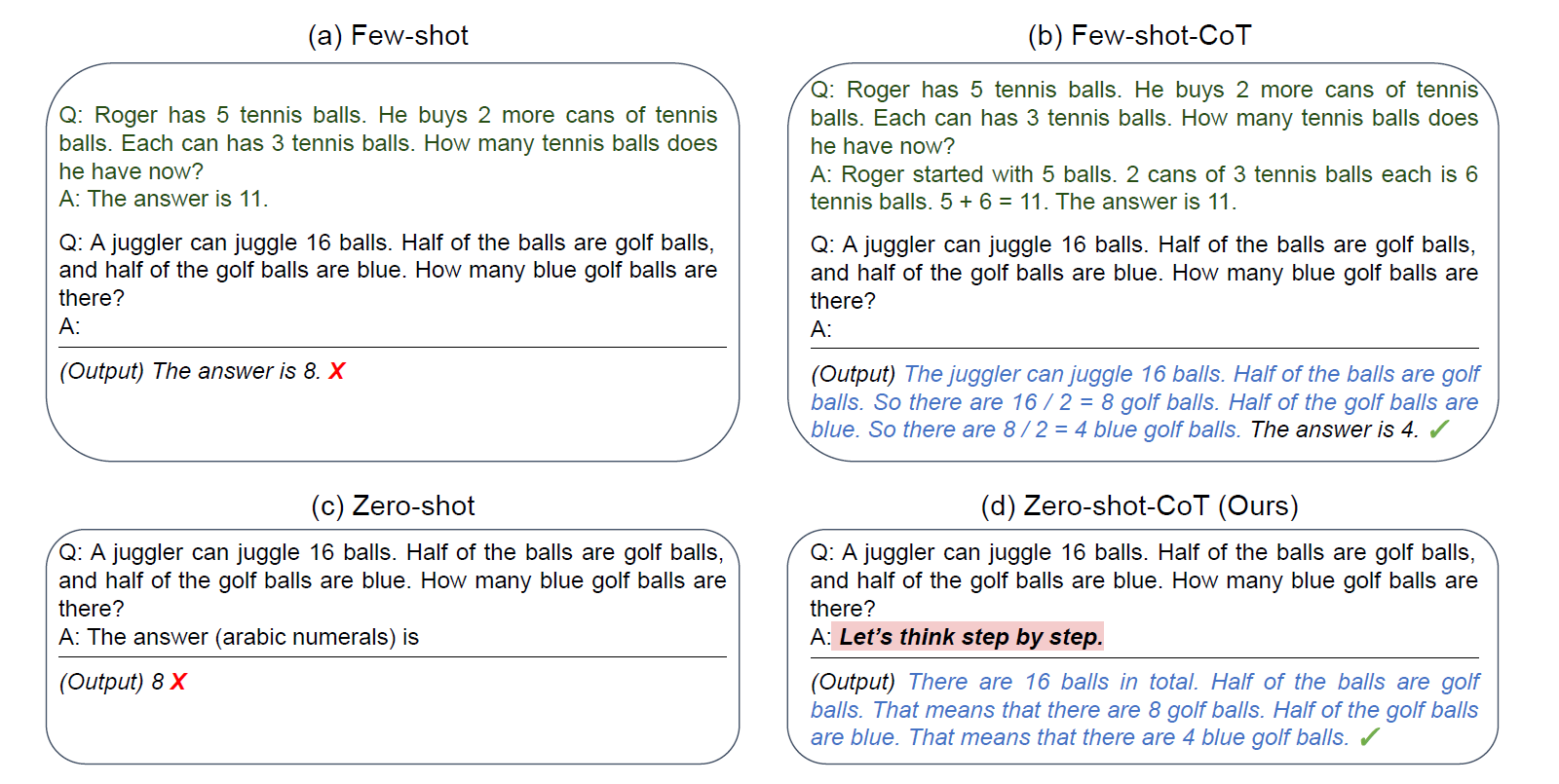

We explore how generating a chain of thought—a series of intermediate reasoning steps—significantly improves the ability of large language models to perform complex reasoning. In particular, we show how such reasoning abilities emerge naturally in sufficiently large language models via a simple method called chain-ofthought prompting, where a few chain of thought demonstrations are provided as exemplars in prompting

They thought Let’s add “reasoning process” before “answer”, explain to the model how it should go about thinking to solve this problem.

Input:

Q: “Elon Musk”

A: the last letter of “Elon” is “n”. the last letter of “Musk” is “k”. Concatenating “n”, “k” leads to “nk”. so the output is “nk”.

Q: “Bill Gates”

A: the last letter of “Bill” is “l”. the last letter of “Gates” is “s”. Concatenating “l”, “s” leads to “ls”. so the output is “ls”.

Q: “Donald John Trump"

Response:

A: the last letter of “Donald” is “d”. the last letter of “John” is “n”. the last letter of “Trump” is “p”. Concatenating “d”, “n”, “p” leads to “dnp”. so the output is “dnp”.

One demonstration is enough, like humans

Input:

Q: “Elon Musk”

A: the last letter of “Elon” is “n”. the last letter of “Musk” is “k”. Concatenating “n”, “k” leads to “nk”. so the output is “nk”.

Q: “Donald John Trump"

Response:

A: the last letter of “Donald” is “d”. the last letter of “John” is “n”. the last letter of “Trump” is “p”. Concatenating “d”, “n”, “p” leads to “dnp”. so the output is “dnp”.

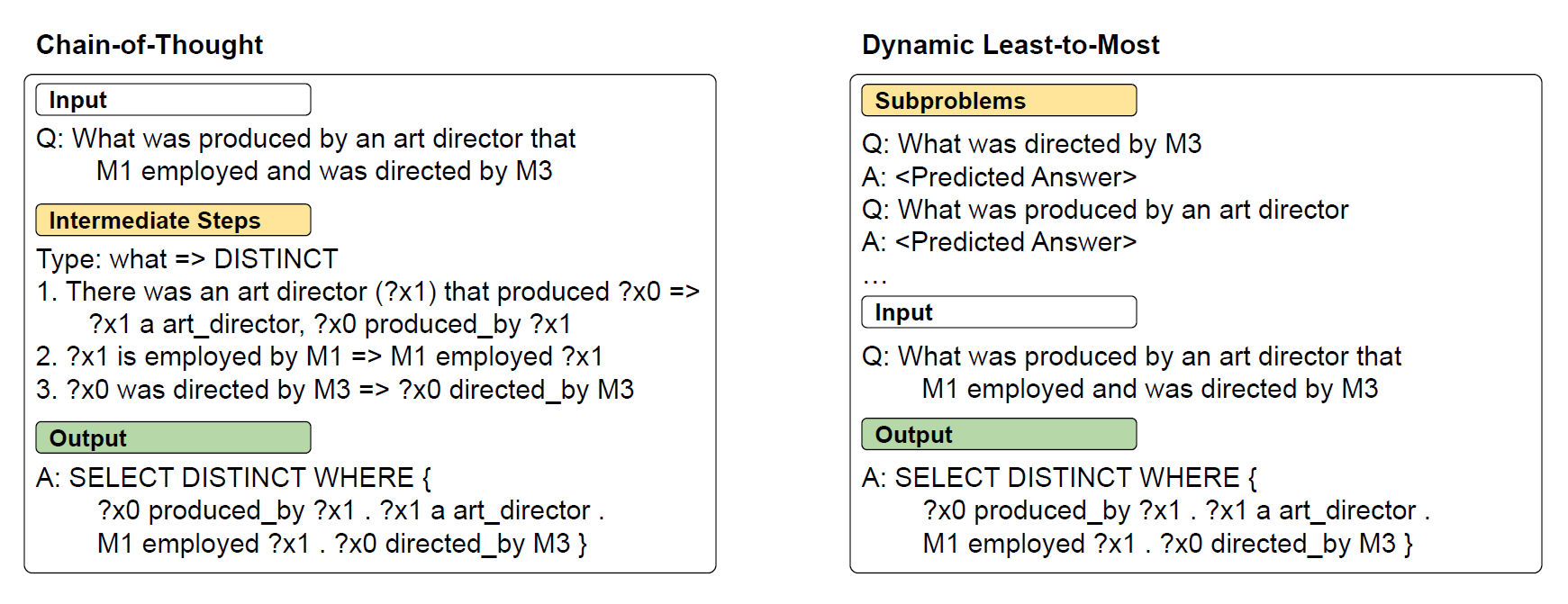

So this is basically Chain of Thought prompting, one of the most powerful ways to interact with an LLM.

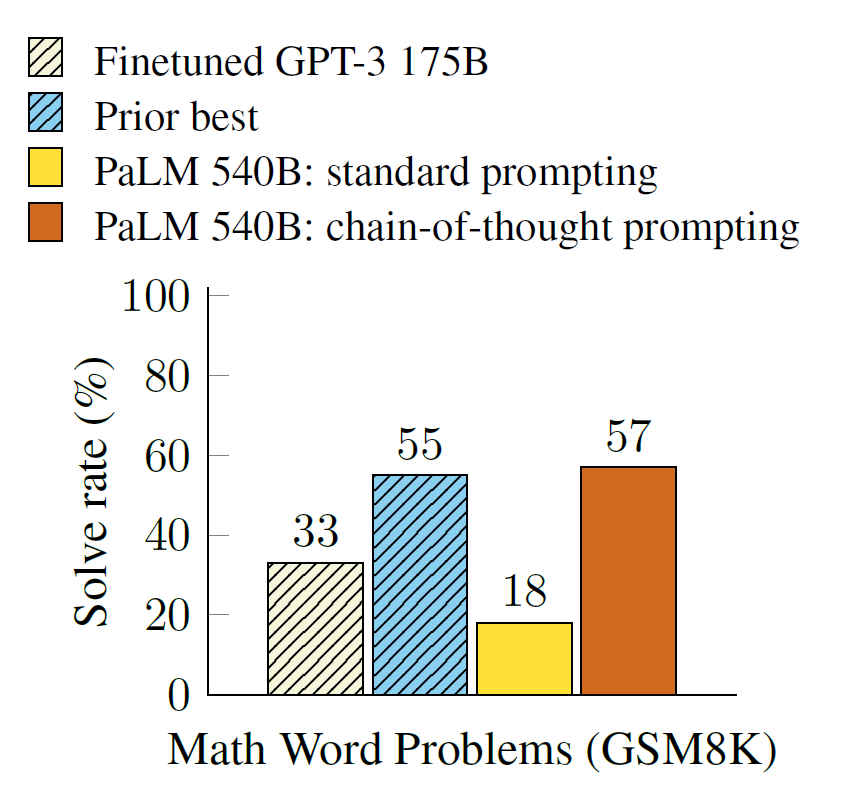

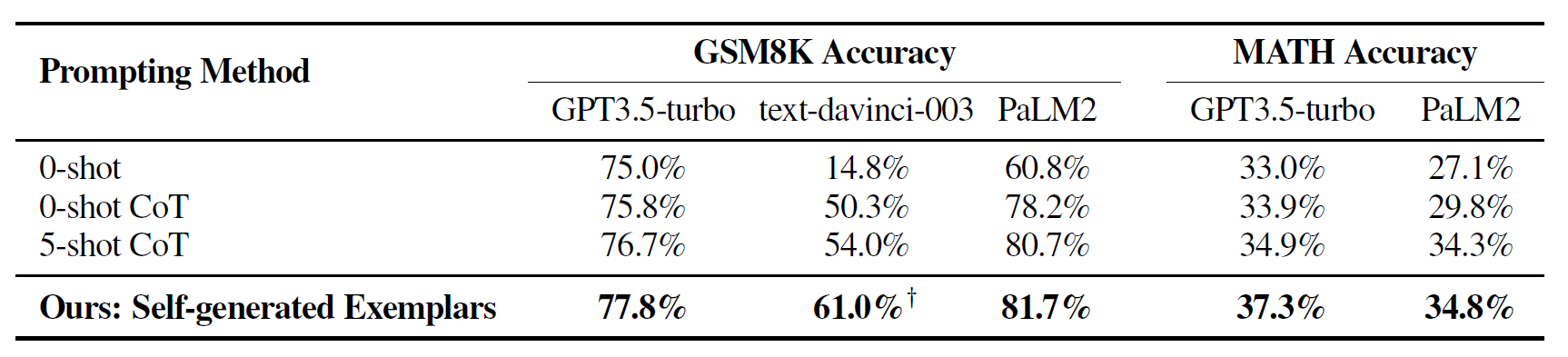

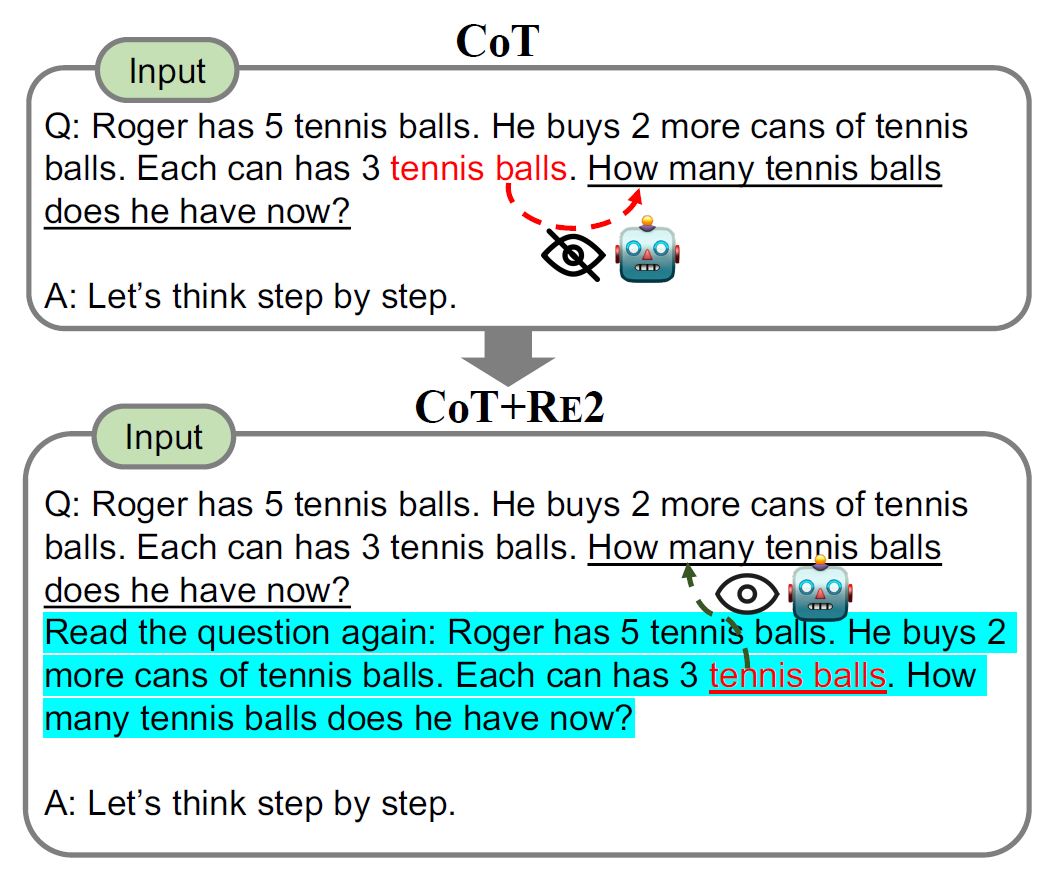

So, CoT is widely considered as the go to prompting stratergy for complex reasoning tasks in the ML Community, and most of the subsiquent research compares its performace to CoT Prompting.

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

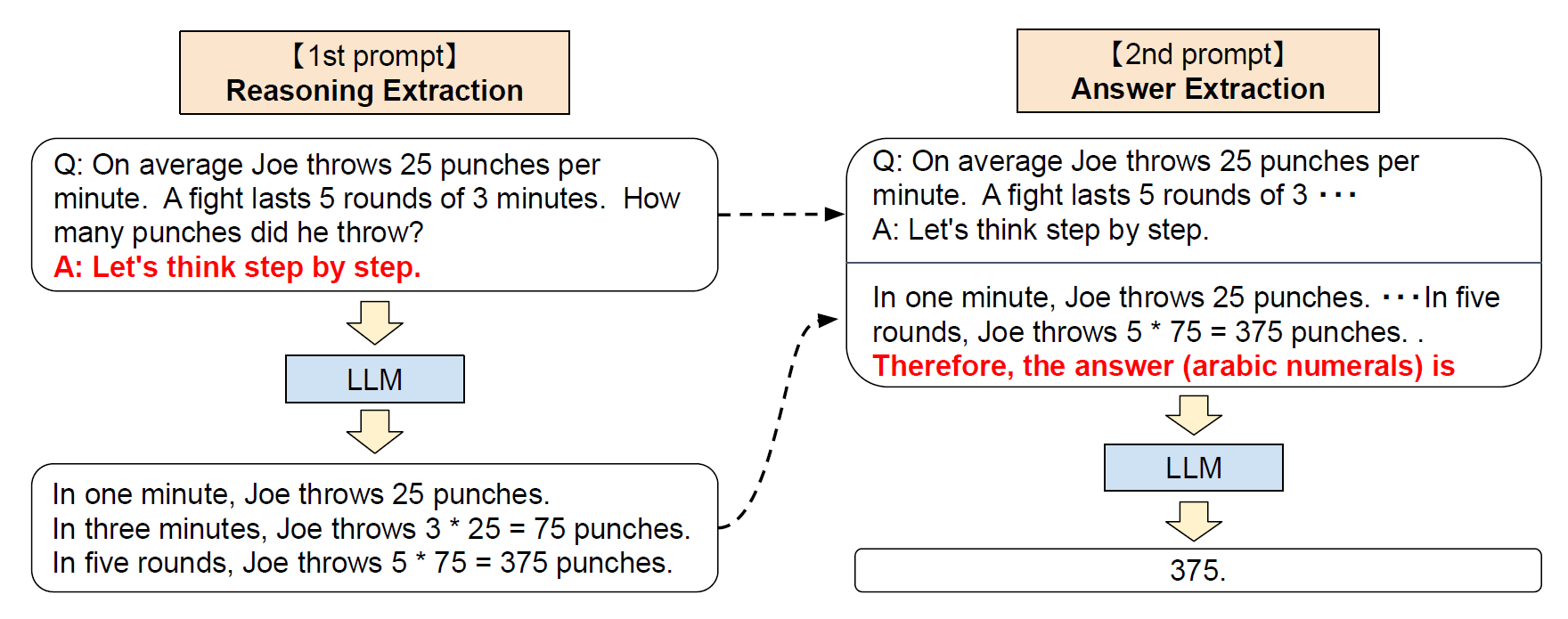

Let’s think step by step

“Prompt Programming for Large Language Models: Beyond the Few-Shot Paradigm”, i think this paper is gulty of giving prompot engineeering the bad rep it has in the research community, just by inserting coluns in place of arrows for language translation and by using, terms like

A French phrase is provided: source_phrase The masterful French translator flawlessly translates the phrase into English:

this definitely didnt help the research community, i think they were a bit mad, cause simple dumb prompts were working wonders, and the $300k prompt engineer memes came flooding in, i wnat to look at the merits of this research…

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

These are some of the fundamentals that you need to know, now Look at some of the latest Research in advanced Reasoning capabilities

A Look at some of the latest Research in advanced Reasoning capabilities

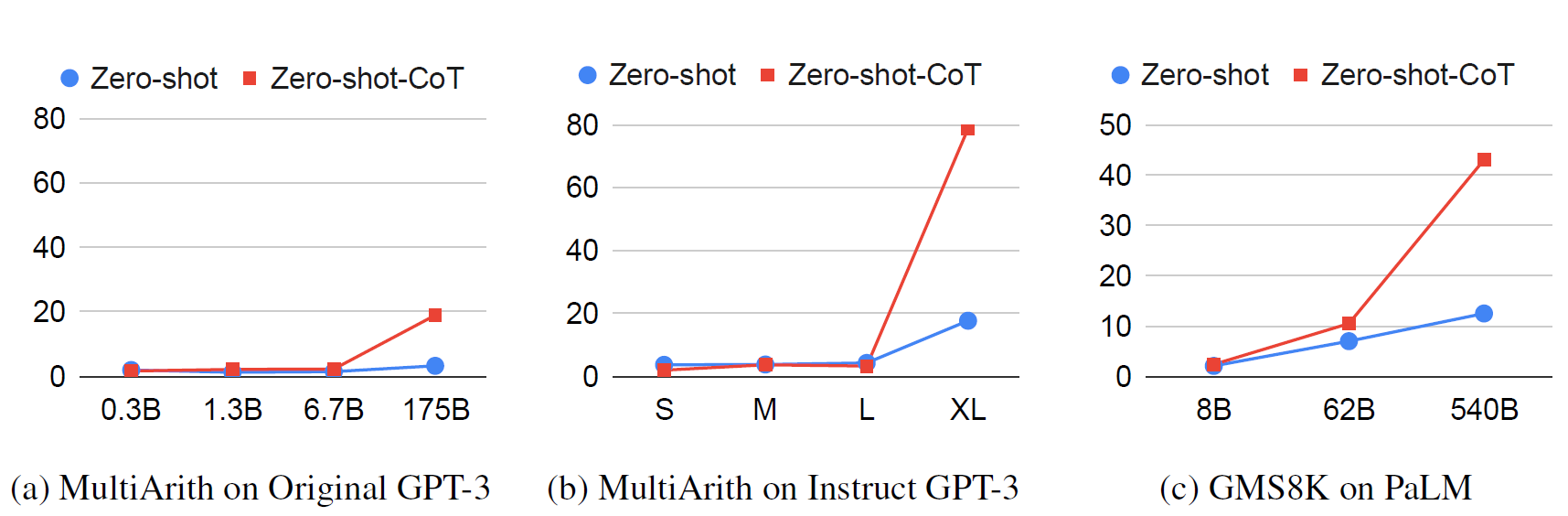

Chain of Thought reasoning and Zero-Shot Chain of thought reasoning, are common ways people try to get most out of the models, now lets look at some of the latest research in Prompting and reasoning that came out over the last couple of years.

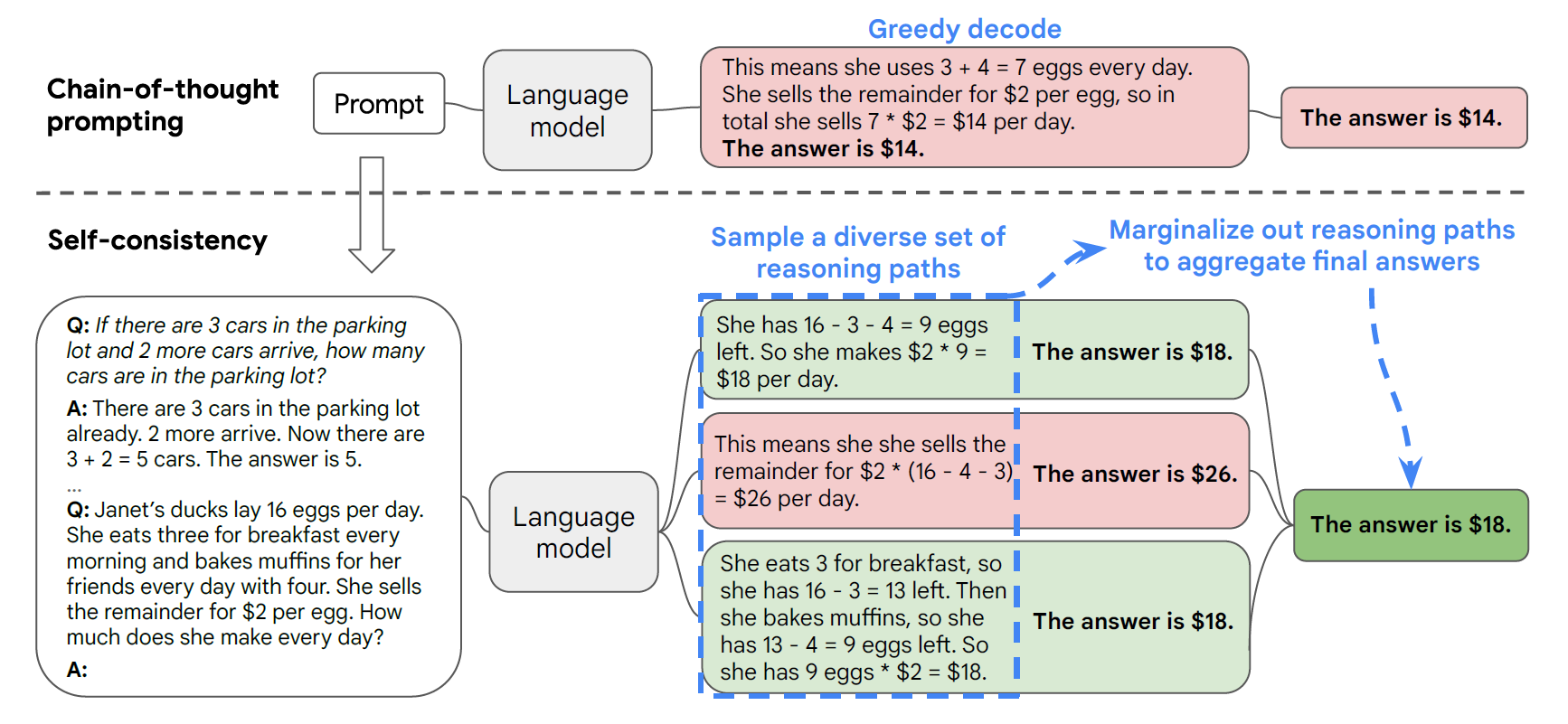

1. SELF-CONSISTENCY IMPROVES CHAIN OF THOUGHT REASONING IN LANGUAGE MODELS (Mar 23)

Self-consistency can be thought of as an, advanced decoding stratergy, i you want to learn some the fundamentals of decoding in language models, you can refer to my post: Decoding in LMs. Self consistency involves sampling a diverse set of solutions for a particualr answer, Self-consistency is compatible with most existing sampling algorithms, including temperature sampling , top-k sampling , and nucleus sampling.

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

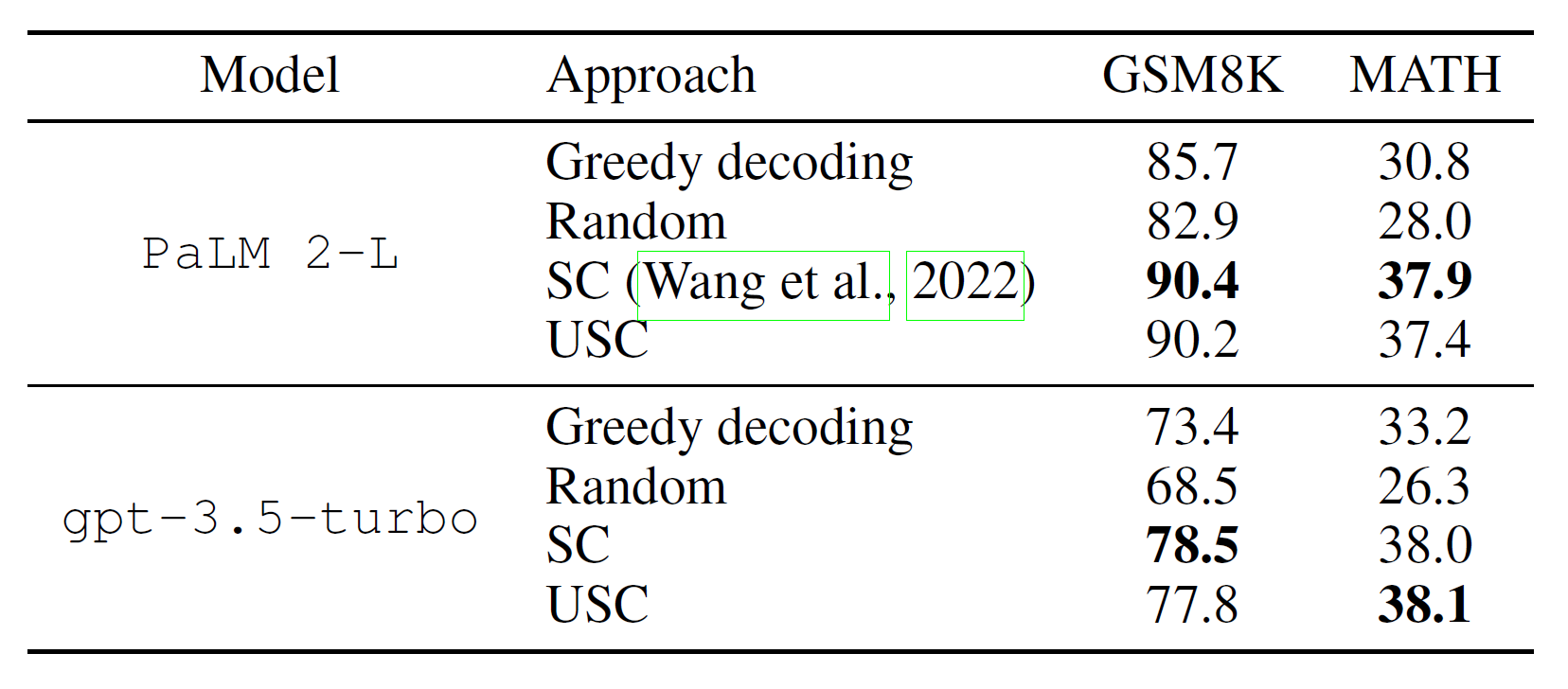

The idea is quite simple, you sample multiple outputs, and the answer which has more concensus is chosen as the answer, as in the above figure $18, occurs 2 out of three times, so this is the answer, but how do you decide which answer to present to the user, the first or the third one? This leads to and important question that we face in LLMs, how do you compare two correct answers, in situation of reasoning, it might be better to present the longer of the two answers, as it might have a more indepth reasoning, but this might not always be correct, so we generally use the answer with the higher normalized probability by the output length.

In Table 1, we show the test accuracy over a set of reasoning tasks by using different answer aggregation strategies. In addition to majority vote, one can also weight each $(r_i, a_i)$ by $P(r_i, a_i \mid \text{prompt, question})$ when aggregating the answers. Note to compute $P(r_i, a_i \mid \text{prompt, question})$, we can either take the unnormalized probability of the model generating $(r_i, a_i)$ given ($\text{prompt, question}$), or we can normalize the conditional probability by the output length (Brown et al., 2020), i.e.,

$$ P(r_i, a_i \mid \text{prompt, question}) = \exp \left( \frac{1}{K} \sum_{k=1}^{K} \log P(t_k \mid \text{prompt, question}, t_1, \ldots, t_{k-1}) \right), $$

where $\log P(t_k \mid \text{prompt, question}, t_1, \ldots, t_{k-1})$ is the log probability of generating the $k$-th token $t_k$ in $(r_i, a_i)$ conditioned on the previous tokens, and $K$ is the total number of tokens in $(r_i, a_i)$.

In Table 1, we show that taking the “unweighted sum”, i.e., taking a majority vote directly over $a_i$ yields a very similar accuracy as aggregating using the “normalized weighted sum”. We took a closer look at the model’s output probabilities and found this is because for each $(r_i, a_i)$, the normalized conditional probabilities $P(r_i, a_i \mid \text{prompt, question})$ are quite close to each other, i.e., the language model regards those generations as “similarly likely”.

Additionally, when aggregating the answers, the results in Table 1 show that the “normalized” weighted sum (i.e., Equation 1) yields a much higher accuracy compared to its unnormalized counterpart. For completeness, in Table 1 we also report the results by taking a “weighted average”, i.e., each $a$ gets a score of its weighted sum divided by $\sum_{i=1}^{m} \mathbb{1}(a_i = a)$, which results in a much worse performance.

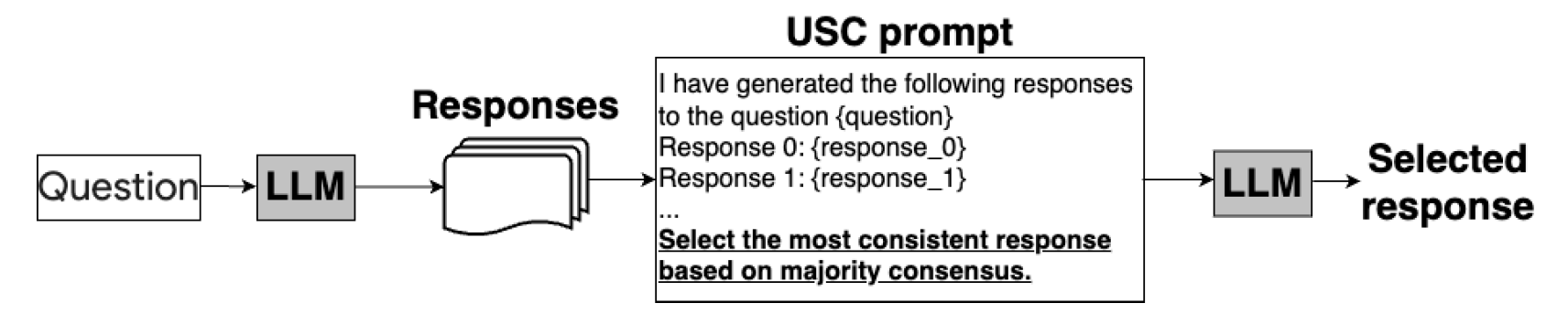

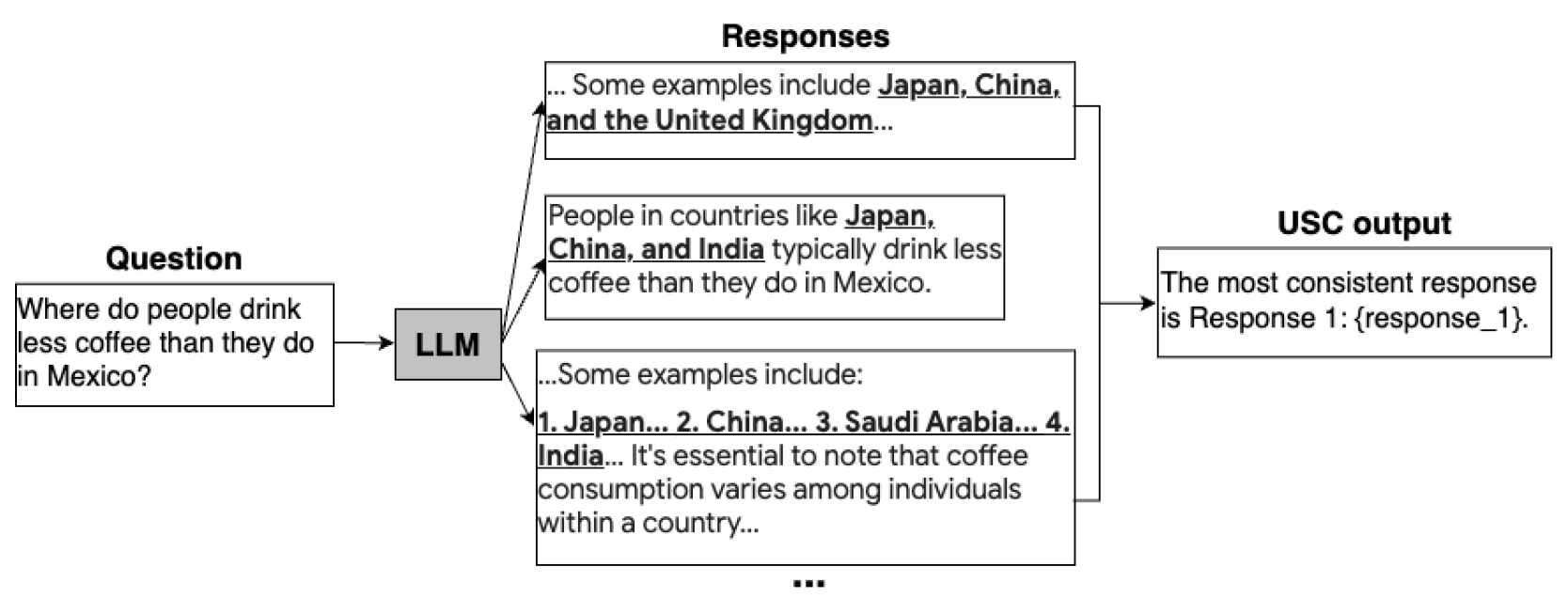

7. UNIVERSAL SELF-CONSISTENCY FOR LARGE LANGUAGE MODEL GENERATION (Nov 23)

self-consistency can only be applied to tasks where the final answer can be aggregated via exact match, e.g., a single number for math problems.

To address this major limitation of self-consistency, we propose Universal Self-Consistency (USC) to support various applications, especially free-form generation tasks. Specifically, given multiple candidate responses, USC simply calls the LLM to select the most consistent response among them as the final output.

The above Self-Consistency frame work is a bit rigid, cause you need the final answer and the best response is determined based on which final answer occurs the most amount of times, but what about problems like text summarization or code generation or open ended quesition answering, wher it is quite difficult to get consistency among different anwers, to remedy this the researchers introduced Universal Self consistency.

This is the first time we are encountering lms evaluating their own generation, this will be a recurring theme among various approaches to prompt engineering, and at the end i will discuss some limitations of llms evaluation their own work, that you should be aware of..

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

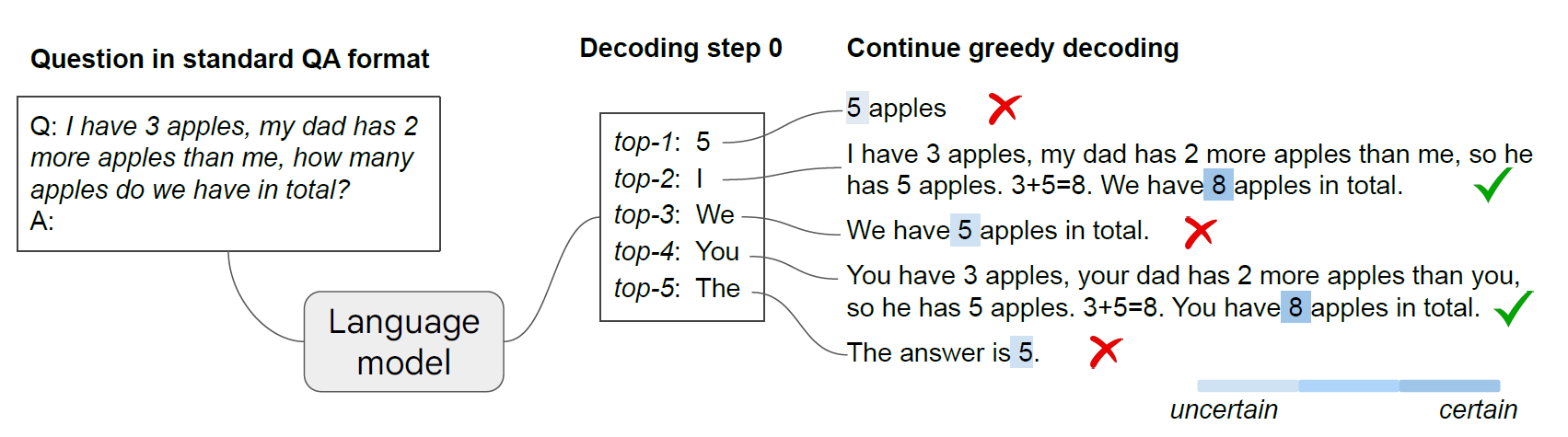

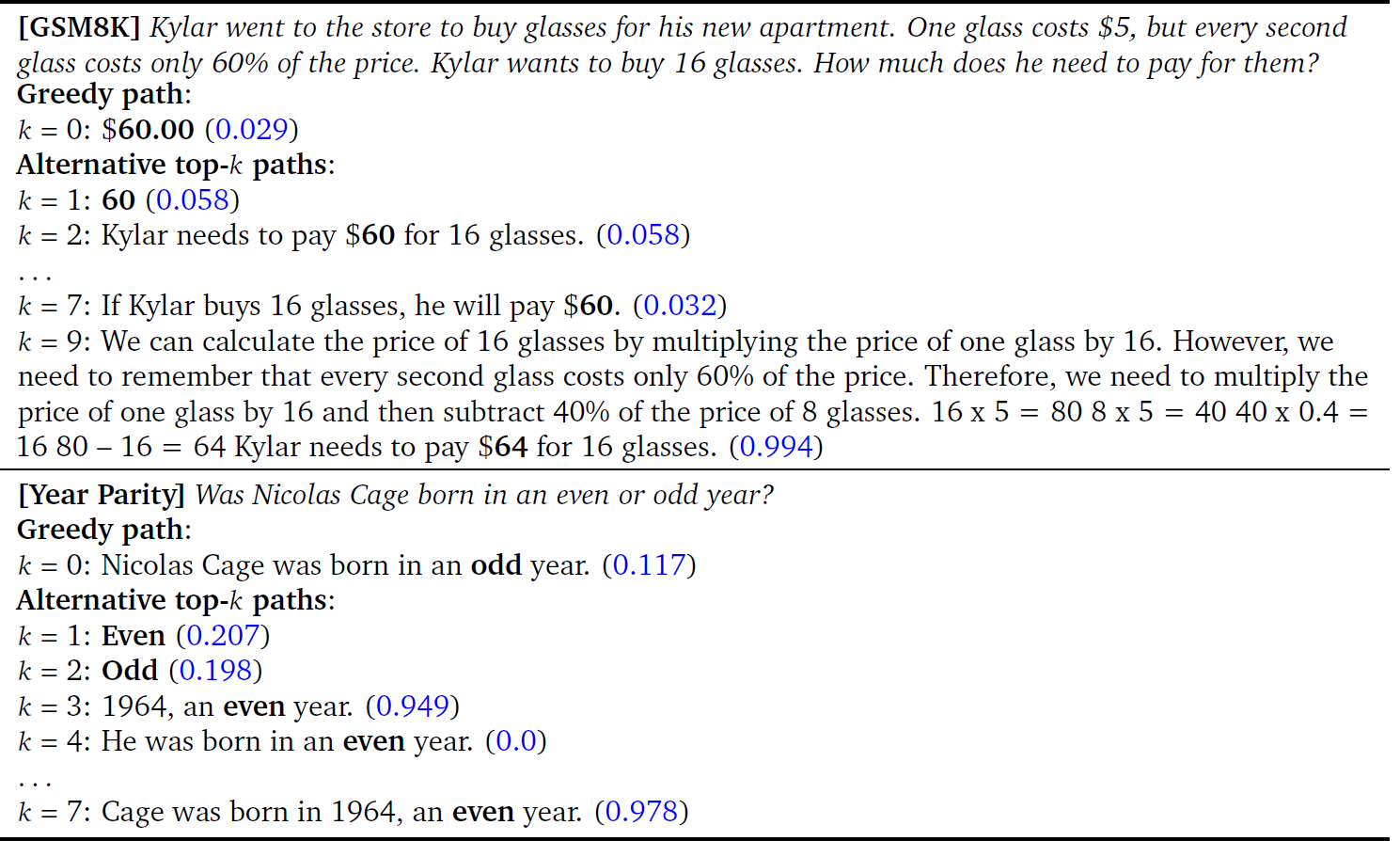

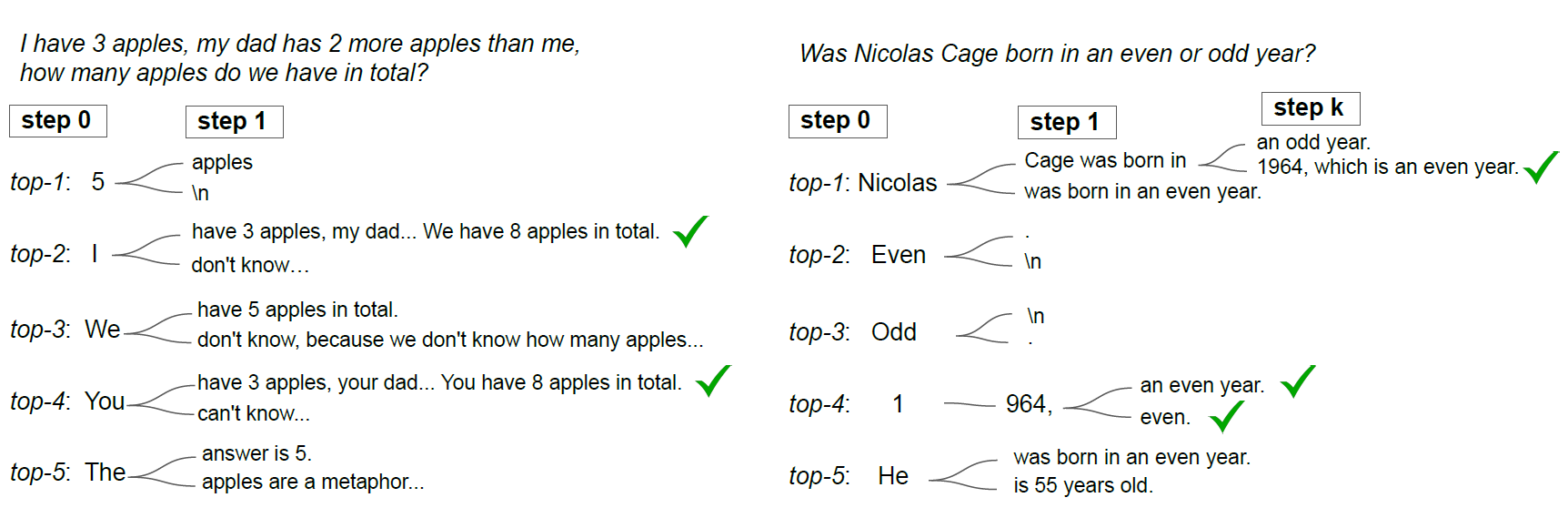

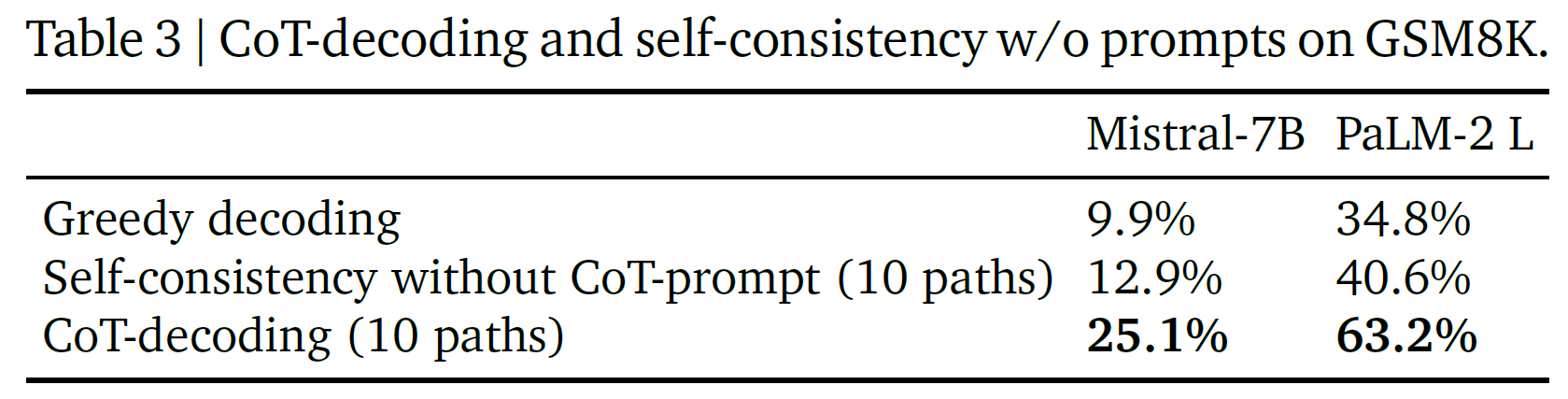

6. Chain-of-Thought Reasoning without Prompting

This is another cool approach, this research is from Google Deepmind, and the researchers behind it are some of the most pieonering in the field of NLP, they

We investigate whether pre-trained language models inherently possess reasoning capabilities, without explicit prompts or human intervention.

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

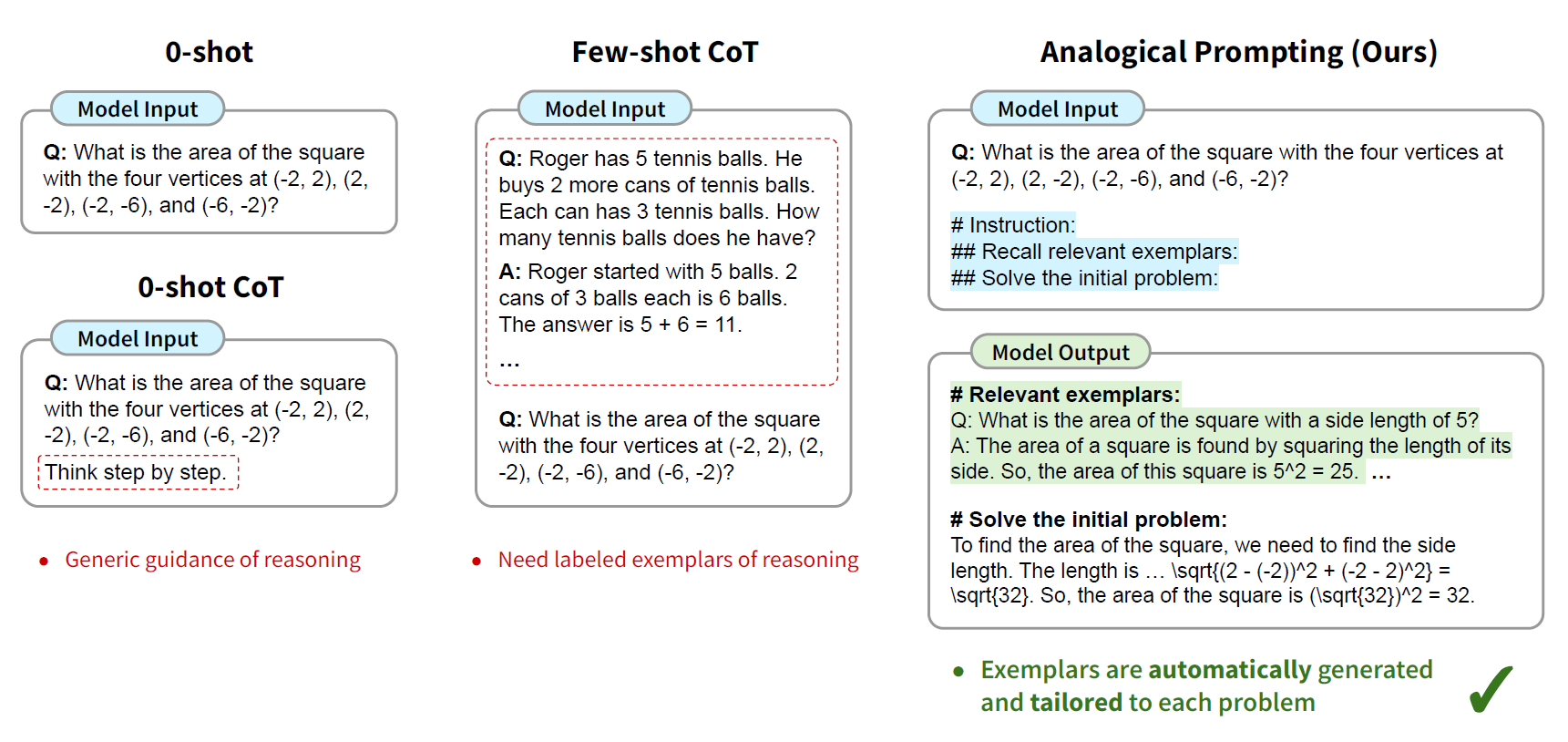

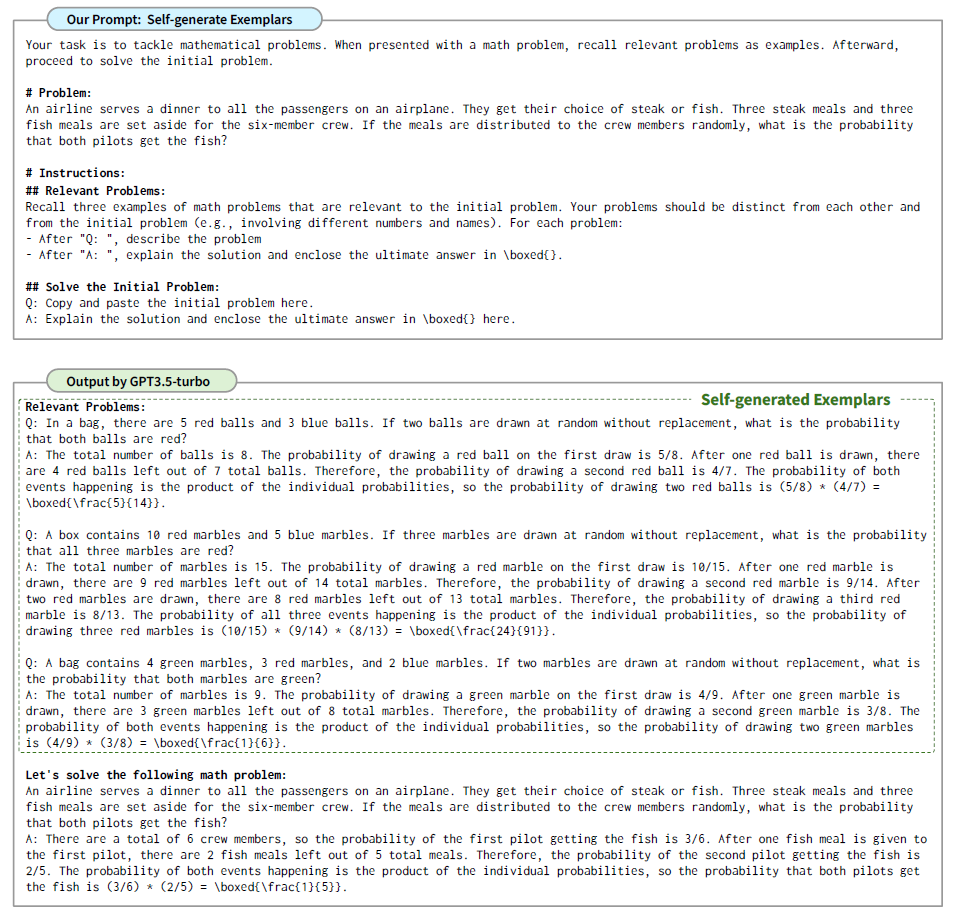

8. LARGE LANGUAGE MODELS AS ANALOGICAL REASONERS ✅

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

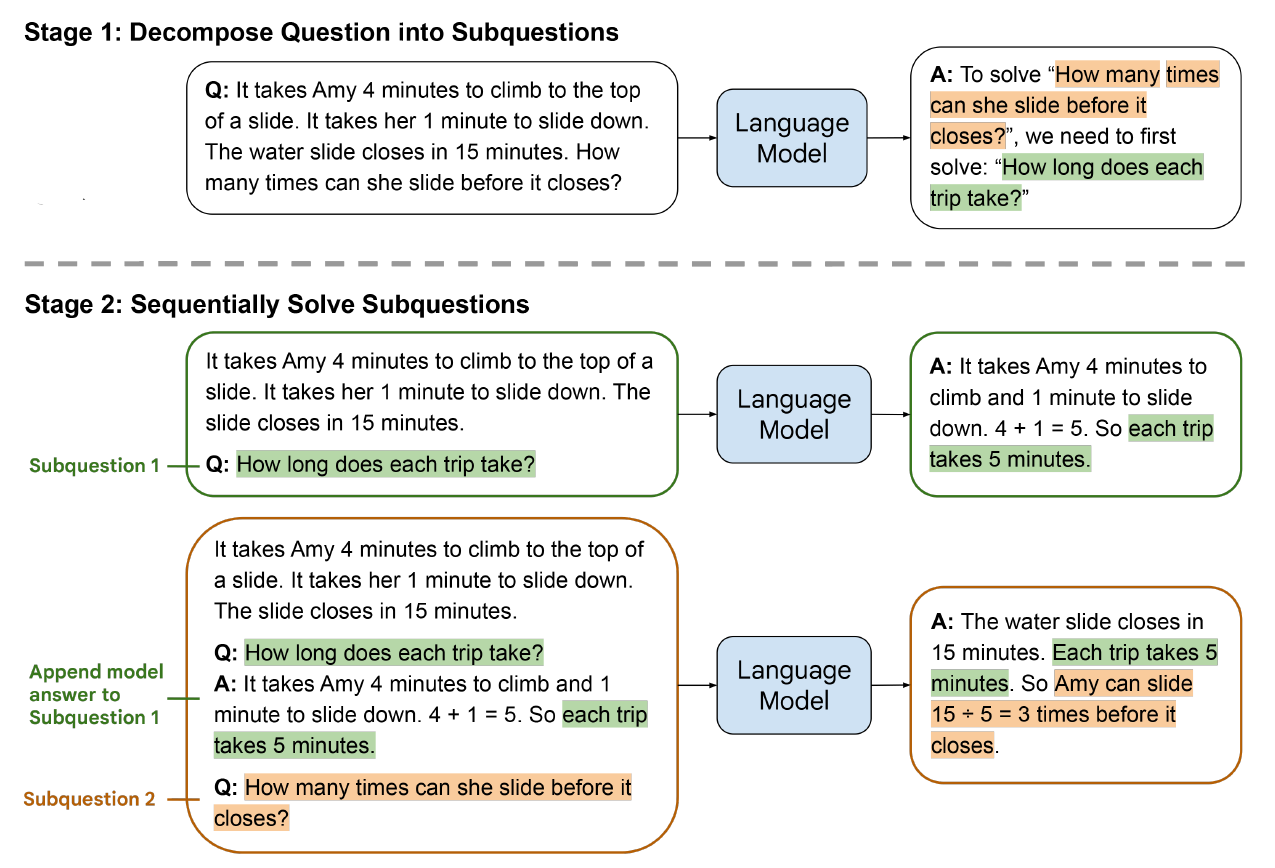

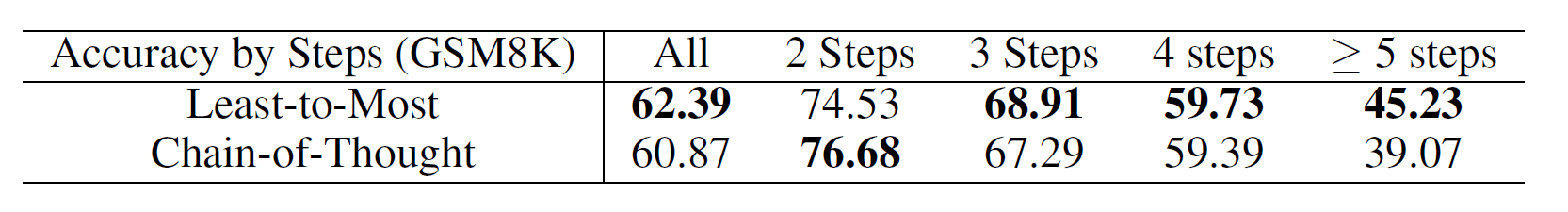

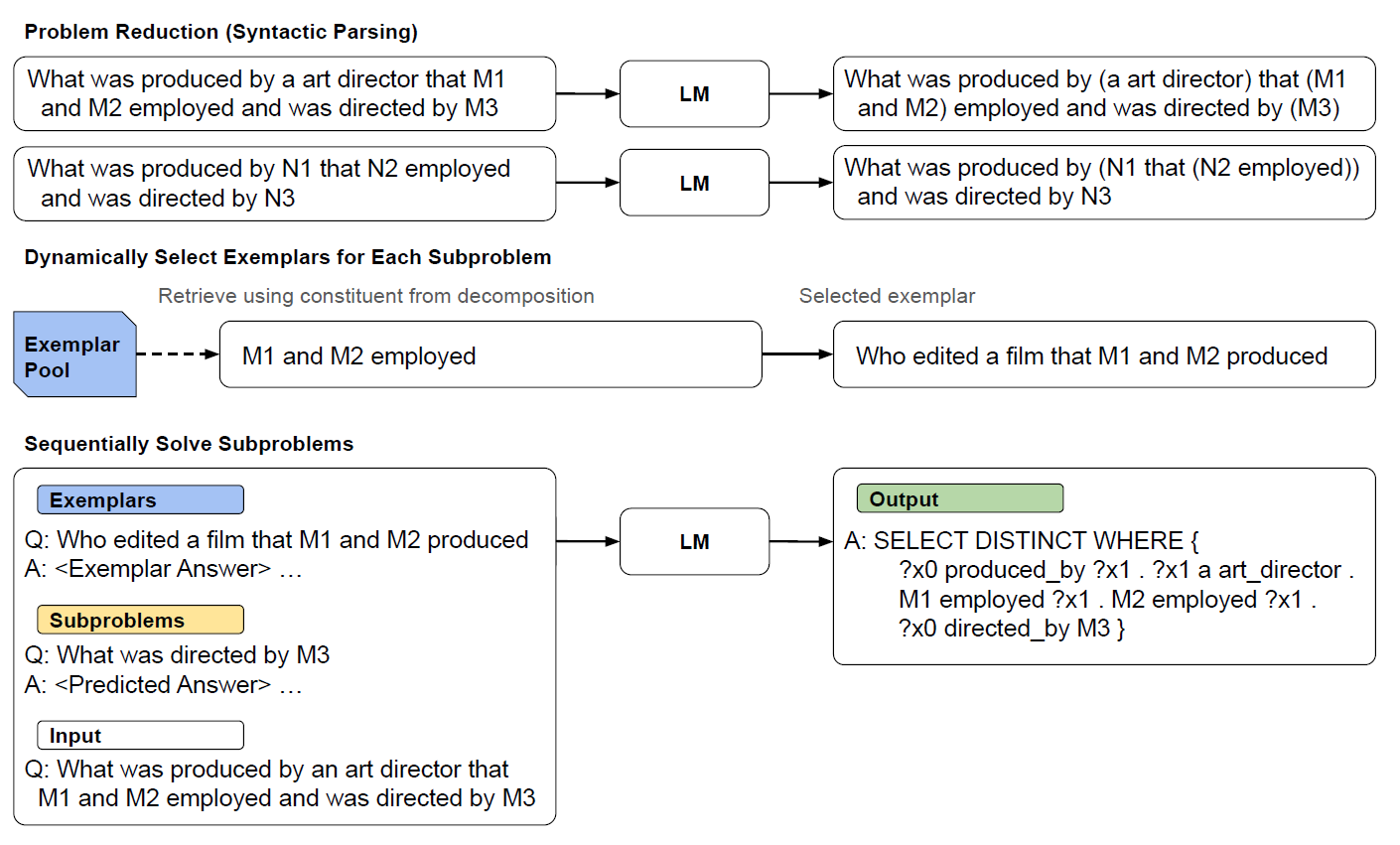

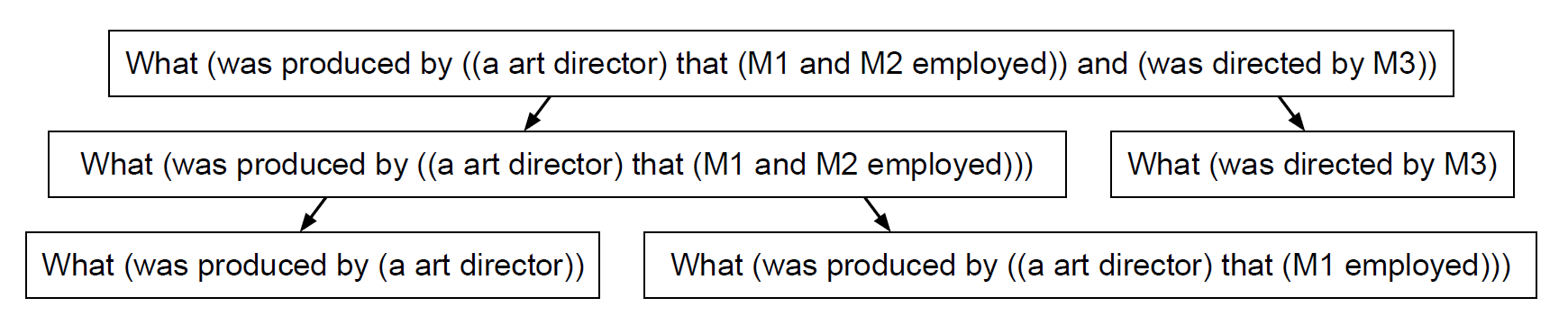

11. LEAST-TO-MOST PROMPTING ENABLES COMPLEX REASONING IN LARGE LANGUAGE MODELS ✅

Chain-of-thought prompting has demonstrated remarkable performance on various natural language reasoning tasks. However, it tends to perform poorly on tasks which requires solving problems harder than the exemplars shown in the prompts.

The key idea in this strategy is to break down a complex problem into a series of simpler subproblems and then solve them in sequence.

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

10. COMPOSITIONAL SEMANTIC PARSING WITH LARGE LANGUAGE MODELS

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

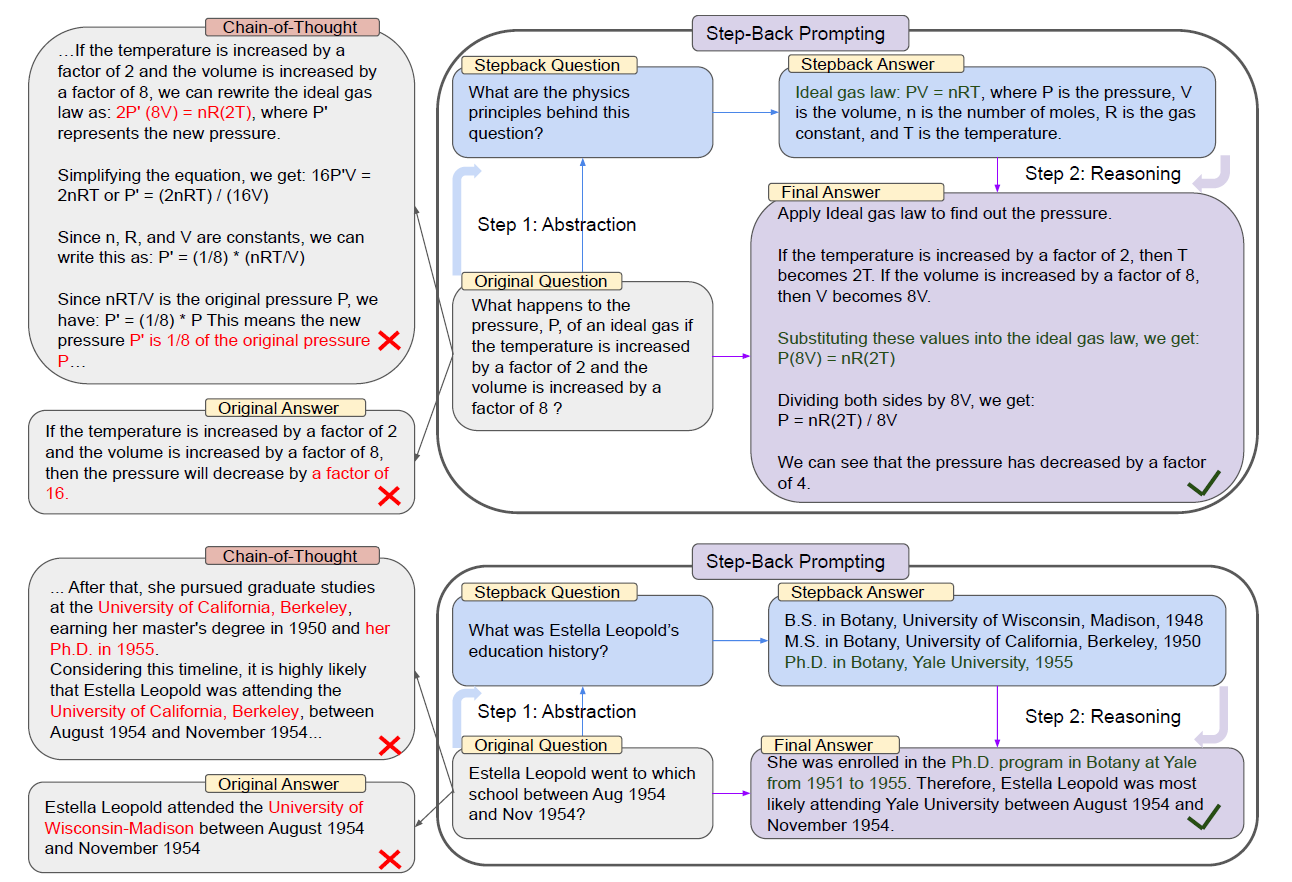

TAKE A STEP BACK: EVOKING REASONING VIA ABSTRACTION IN LARGE LANGUAGE MODELS

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

Re-Reading Improves Reasoning in Large Language Models

A quite simple but elegant idea,

Figure 1: Comparison of FP8 and BF16 formats. Source: Smith et al. (2023)

Limitations

Till Now we have looked, what LLMs can do with proper prompting techniques,

4. Large Language Models Can Be Easily Distracted by Irrelevant Context ✅

Prompting large language models performs decently well in a variety of domains However, for most of theses evaluation benchmarks, all the information provided in the problem description is relevant to the problem solution, as the problems in exams. This is different from real-world situations, where problems usually come with several pieces of contextually related information, which may or may not be relevant to the problems that we want to solve. We have to identify what information is actually necessary during solving those problems.

5. LARGE LANGUAGE MODELS CANNOT SELF-CORRECT REASONING YET ✅

Self-Refine: Iterative Refinement with Self-Feedback

Reflexion: Language Agents with Verbal Reinforcement Learning

3. TEACHING LARGE LANGUAGE MODELS TO SELFDEBUG

2. Premise Order Matters in Reasoning with Large Language Models ✅

Do Language Models Know When They’re Hallucinating References?

Prompt Templates

This is also a fundamental thing that prompt engineers need to understand, lets just look at the open ai template, will not discuss this in greater detail, cause not that intresting, ill provide references for LLama and Anthropic prompt templates.

New Stuff

Motivation for Reasoning

I’ve dedicated significant time and effort to studying classical machine learning algorithms like Linear Regression, Support Vector Machines, and K-Nearest Neighbors. However, what sets today’s field of AI apart from previous generations is the ability of modern models to reason—or do something that convincingly resembles reasoning. The ideal of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) envisions a computer that can reason and plan ahead. Current large language models (LLMs) can be taught to perform a wide variety of tasks, primarily through the paradigm of prompt engineering.

The ability to reason is transformative. Let’s imagine it’s 2020, before LLMs became mainstream, and you want to solve the following problem:

Last Letter Concatenation

| Input | Output |

|---|---|

| “Elon Musk” | “nk” |

| “Bill Gates” | “ls” |

| “Barack Obama” | ? |

Rule: Take the last letter of each word and concatenate them.

Even though this is a toy problem, it provides fundamental concepts necessary to understand how LLMs reason. Most people would collect vast amounts of data and try to train a model to perform this simple task. This approach is a massive waste of time and resources, as a human can write a simple program to solve it. In contrast, an ML model might require thousands of examples to get it right.

Enter LLMs

From the paper “Language Models are Few-Shot Learners,” we know that LLMs can provide correct answers based on just a few examples. Let’s see how ChatGPT handles the problem:

Initially, the model might not recognize the pattern. Instead of concluding that the task cannot be solved by the LM, researchers enhanced the model by introducing a “reasoning process” before the answer.

Example:

Q: “Elon Musk”

A: The last letter of “Elon” is “n.” The last letter of “Musk” is “k.” Concatenating “n” and “k” leads to “nk.” So, the output is “nk.”

Q: “Bill Gates”

A: The last letter of “Bill” is “l.” The last letter of “Gates” is “s.” Concatenating “l” and “s” leads to “ls.” So, the output is “ls.”

Q: “Barack Obama”

A: The last letter of “Barack” is “k.” The last letter of “Obama” is “a.” Concatenating “k” and “a” leads to “ka.” So, the output is “ka.”

One demonstration is enough, much like it is for humans.

Example:

Q: “Elon Musk”

A: The last letter of “Elon” is “n.” The last letter of “Musk” is “k.” Concatenating “n” and “k” leads to “nk.” So, the output is “nk.”

Q: “Barack Obama”

A: The last letter of “Barack” is “k.” The last letter of “Obama” is “a.” Concatenating “k” and “a” leads to “ka.” So, the output is “ka.”

This approach achieves 100% accuracy with only one demonstration example. This is essentially Chain-of-Thought prompting, one of the most powerful ways to interact with an LLM.

Language Models are Few-Shot Learners

Let’s move away from this toy example and examine one of the seminal papers in AI, “Language Models are Few-Shot Learners” (commonly referred to as the GPT-3 paper). This paper introduces terms like “in-context learning” and provides examples of few-shot and zero-shot learning, highlighting how they differ from fine-tuning.

In-Context Learning

A Better Explanation:

During unsupervised pre-training, a language model develops a broad set of skills and pattern recognition abilities. It then uses these abilities at inference time to rapidly adapt to or recognize the desired task. We use the term “in-context learning” to describe the inner loop of this process, which occurs within the forward pass upon each sequence. The sequences in this diagram are not intended to represent the data a model would see during pre-training but are meant to show that there are sometimes repeated sub-tasks embedded within a single sequence.

Zero-Shot, One-Shot, and Few-Shot Learning, Contrasted with Traditional Fine-Tuning

Let’s look at the difference in performance observed by researchers:

Few-shot learning with around 10 examples provides the best results.

Chain-of-Thought Prompting

These fundamentals are essential for everyone to understand. Let’s explore some of the other pioneering work in the field.

The paper “Prompt Programming for Large Language Models: Beyond the Few-Shot Paradigm” is partly to blame for the bad reputation prompt engineering has in the research community. By inserting colons in place of arrows for language translation and using terms like:

A French phrase is provided: source_phrase

The masterful French translator flawlessly translates the phrase into English:

This approach didn’t help the research community. Simple, straightforward prompts were working wonders, leading to memes about $300k prompt engineers flooding in. I want to examine the merits of this research…

Unsupervised Chain-of-Thought Prompting

To be continued…

I’m working on a blog about prompt engineering, and this is my initial draft. I’ve made several improvements, particularly in the opening paragraph, while maintaining the original tone and intent. Let me know if you have any further suggestions or areas you’d like to refine!

Drafts

Language Models are Few-Shot Learners

So now that we have be motivated and suffiently familiar with zero shot, few shot and CoT prompting, lets look at some more important concepts, and try and understand why techniques like Few shot prompting work. Lets move away from this toy Example and look at one of the seminal papers in the field of AI, “Language Models are Few-Shot Learners”, (more commonly reffered to as the GPT-3 paper). Here they introduce terms like “in-context learnign” and provided examples of few shot and zero shot learnign and how it differs from finetuning.

In-context learnign

a better explanation

Zero-shot, one-shot and few-shot, contrasted with traditional fine-tuning

So, lest look at the difference in performance the researchers observed,

So, few shot with around 10 examples provide the best results.

Chain-of-Thought Prompting

so the above are the fundamentals that every-one need to understand, lets look at some of the other pienoering work..